In an attempt to detect whether a network can hijack DNS queries, Google’s Chrome browser and its Chromium-based counterparts randomly conjure up three domain names to be checked between 7 and 15 characters, and if two domain answers return the same Address, the browser assumes the network catches and redirects non-existent domain requests.

This check will be performed upon initialization, and if the IP or DNS settings of a system alter.

Due to the way DNS servers move through locally unknown domain queries to more authoritative name servers, Chrome’s random domains find their way up to the root DNS servers, and according to Verisign ‘s main engineer at CSO ‘s applied research division, Matthew Thomas, those queries make up half of all root server queries.

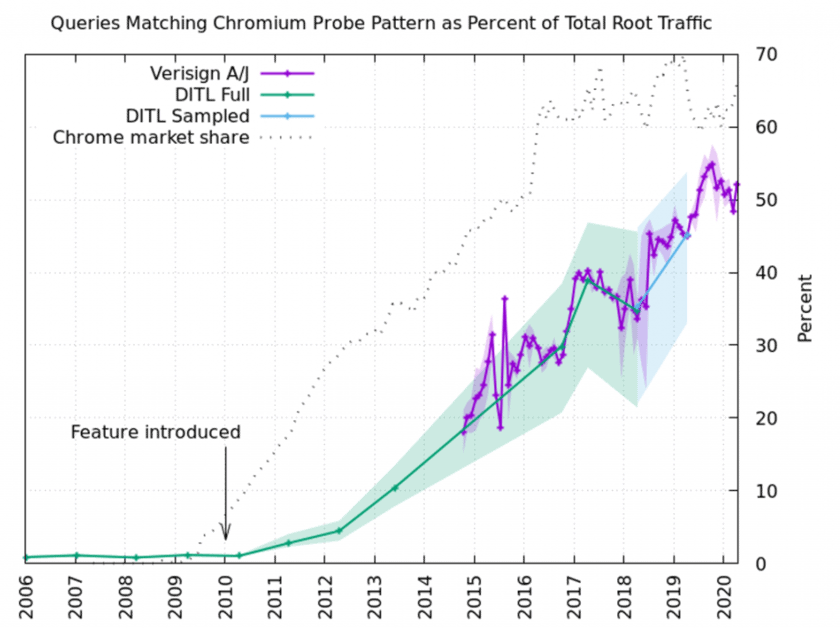

Data provided by Thomas showed that, as market share for Chrome grew after the feature was introduced in 2010, queries following the pattern used by Chrome grew similarly.

“We now find in the 10-plus years since the functionality was introduced that half of the DNS root server traffic is most likely due to probes from Chromium,” Thomas said in a blog post on APNIC. “This is equal to about 60 billion root server machine queries on a typical day.”

Thomas added that half the root server’s DNS traffic is used to support a single user feature, and with DNS surveillance being “surely the exception rather than the standard,” the traffic would be a distributed denial of service attack in any other case.

Earlier this month, research dean Johannes Ullrich of the Sans Institute looked at how many of the world’s 2,7 million authoritative name servers will be required to remove 80 percent of the internet.

“Only 2,302 name servers or around 0.084 percent are required!” Ullrich wrote.

“Name servers account for 90 per cent of all domain names.”

Ullrich found that GoDaddy had 94.5 million records, that Google Domains had 20 million, that the trio of dns.com, hichina, and IONOS had 15.6 million records each, while Cloudflare had 13.8 million records.

“The use of a cloud-based DNS service is easy and sometimes more robust than running your name server, but this broad concentration of name services with few entities significantly increases the network risk,” he said.

To reduce the risk of a service collapse that makes parts of the internet unavailable, Ullrich said people should run in-house secondary name servers, and make sure they use more than one DNS provider.

Telstra provided an example of how a DNS failure could appear to customers as an internet outage, in which case the telco successfully carried out a denial of service attack on itself.

“Our security teams have investigated the huge messaging storm that portrayed it as a denial of service cyber attack, and we now believe it was not malicious, but a domain name server problem,” the telco said at the beginning of the month.

Leave a Reply